Setting Standards

The disclosure of chemicals used in hydraulic fracturing provides an example of the evolution of the standard for disclosure of information. The Frac Focus Chemical Disclosure Registry (FracFocus), a joint project of the Groundwater Protection Council and the Interstate Oil and Gas Compact Commission, began as a site for voluntary disclosure of information. Under intense public pressure for more transparency, some states, including Utah and Colorado, now require operators to disclose the chemicals they use, often to the FracFocus website. The Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is also considering requiring disclosure of hydraulic fracturing chemicals through FracFocus.

Among private companies, some voluntarily disclose their chemicals. For example, Encana voluntarily discloses its chemicals with Frac Focus. Noble also participates in Frac Focus. Halliburton plans to introduce chemical standards for itself.

Bonding

Much like general contractors, oil and gas companies are required to secure a bond before beginning a development project. This bond is typically made payable to the appropriate state or federal oil and gas agency. If the company fails to comply with its obligations (usually to plug wells and restore the development site), the bond is forfeited to cover these costs.

The BLM bond amounts for state and national operations and individual projects were set in 1951 and 1960 respectively, so they are now often substantially lower than the costs they are intended to cover. According to the GAO in Oil and Gas Bonds: Bonding Requirements and BLM Expenditures to Reclaim Orphaned Wells, the federal government has spent millions of dollars on reclaiming “orphaned” wells (those that have not been appropriately dealt with by their operators, and whose costs exceed their bond amounts).

Bonding rules vary from state to state and can be found on our state “law and policy” pages. States often have more recent bonding rules that require higher dollar amounts, as compared with BLM bonds. Notably, Colorado’s COGCC also has the power to award money to surface owners beyond the amount of the initial bond, if it is required to remediate surface damage.

Inspections, Reporting, and Penalties

Most states and federal agencies require oil and gas companies to retain specific records of their activities, which are to be made available to the appropriate regulatory agencies. These agencies also conduct on-site inspections, which can include records checks as well as leak detection, and checking for compliance with other standards.

Which level of government (federal or state) and which agency (federal land management agency, state oil and gas commission or federal or state environmental agency) regulates depends on the ownership of the lands and minerals being developed and on the law being enforced.

Subsurface mineral rights and surface rights for a piece of land may be owned separately; this is called a “split estate”. In the intermountain region, most oil and gas developments take place on federal land or concern federally owned mineral rights under private land. In those situations, the BLM applies federal oil and gas regulations. State oil and gas regulations apply where the land and minerals are private and can apply on federal land and minerals as well. Whether rules governing air and water protection or waste management are enforced by a federal or state agency depends on whether the state has “primacy” regarding a particular law (e.g., the federal Clean air Act or Clean Water Act) and whether the state law is more stringent than the federal law. (See the Law and Policy pages for more information on the interaction of federal and state regulation and for specific federal and state laws.)

Federal Enforcement

The major federal agencies involved in assuring regulatory compliance for oil and gas development are the BLM and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Bureau of Land Management

The BLM’s inspection and enforcement program mostly conducts environmental inspections. According to the GAO in a 2014 report, Oil and Gas: Updated Guidance, Increased Coordination, and Comprehensive Data Could Improve BLM’s Management and Oversight, the BLM has failed to adequately inspect because of a lack of coordination with state officials, lack of funding and staff, and reliance on old guidelines. See BLM’s penalties for noncompliance at 43 C.F.R. § 3163.

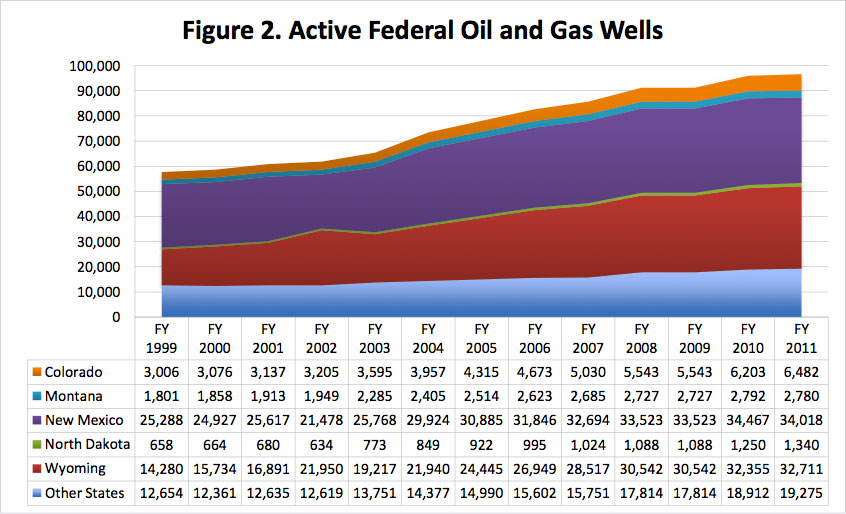

Despite conducting thousands of inspections each year (over 33,000 in 2011), a 2014 GAO report, Oil and Gas: Updated Guidance, Increased Coordination, and Comprehensive Data Could Improve BLM’s Management and Oversight, finds that the BLM has failed to adequately inspect because of a lack of coordination with state officials, lack of funding and staff, and reliance on old guidelines.

Environmental Protection Agency

The EPA operates several programs related to monitoring and compliance, including an air pollution monitoring program and a water quality monitoring program. EPA’s Office of Enforcement and Compliance Assurance (OECA) addresses monitoring and compliance during oil and gas development by working with EPA regional offices, and in partnership with state and tribal governments, and other federal agencies to enforce the nation’s environmental laws, including the Clean Water Act, Clean Air Act and Safe Drinking Water Act.

According to EPA, compliance monitoring is one of the key components that EPA uses to protect human health and the environment by ensuring that the regulated community obeys environmental laws/regulations through on-site visits by qualified inspectors, and a review of the information EPA or a state/tribe requires to be submitted. EPA and its regulatory partners conduct inspections under the majority of statutory and regulatory programs, although the Clean Air Act requires evaluations rather than inspections. EPA also promotes compliance incentives and auditing to encourage facilities to find and disclose violations to the Agency. Violations may also be discovered from tips/complaints received by the Agency from the public. Violations discovered as a result of any of these activities may lead to civil enforcement or criminal enforcement. The Agency also provides compliance assistance to the regulated community to help them understand their requirements and to minimize or prevent violations from occurring at regulated facilities. EPA's reporting requirements are also important for understanding and minimizing the impacts of oil and gas development. The EPA’s Greenhouse Gas Reporting Program took effect in 2010, and requires companies, including owners or operators of facilities that contain petroleum and natural gas systems, to calculate and report their greenhouse gas emissions.

State Enforcement

State enforcement of laws governing oil and gas development also relies on the interactions of oil and gas and environmental agencies. State oil and gas agencies generally set standards for development activities and have the authority to conduct inspections, levy fines, and even shut oil and gas projects down. A state’s environmental agency will often have additional responsibilities regarding air and water quality protection. For example, Colorado’s Air Quality Control Commission, as part of a multi-stakeholder process with several oil and gas companies, recently developed new rules to monitor and regulate emissions from oil and gas development.

2012 Earthworks report criticized the COGCC's enforcement of its own rules

When a state agency finds a violation as a result of its monitoring process, the enforcement process begins. While the process differs among the states, Colorado’s Oil and Gas Conservation Commission (OCGCC) recently modified enforcement program is used to illustrate this process. The new enforcement program , responding to a governor’s directive to improve the enforcement process, emphasizes the three principles of transparency, consistency, and compliance. For an administrative violation, the COGCC may take the discretionary (warning letter) or mandatory Notice of Alleged Violation (NOAV) path. For a field violation, the COGCC will complete a Field Inspection Report (FIR). It may then take the discretionary (“Corrective Action Required” FIR) path or the mandatory (“Violation” FIR-NOAV) path. NOAV and Enforcement related questions are answered here. “COGCC Rule Characterizations and Enforcement Designations” are explained here.

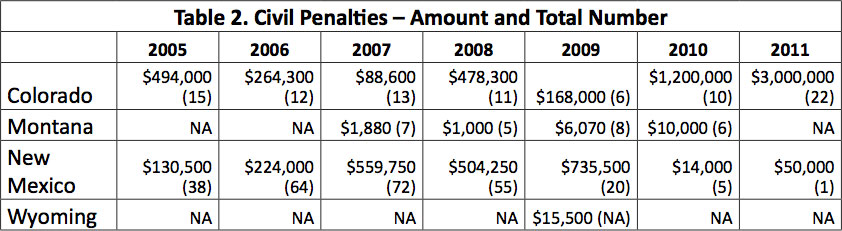

A list of the COGCC’s imposed penalties for the first quarter of 2014 is available here. As in other Intermountain states, the number and dollar amount of these penalties is fairly low. (See the Law and Policy pages for each state for the relevant provisions for penalties assessed by regulatory agencies.) See the Colorado Local page for relevant provisions for penalties assessed by local municipalities. Across the board, the financial penalties are too low to disincentivize violations, but this is starting to change. For example, Colorado’s Governor Hickenlooper signed a bill into law on June 6, 2014 that raised the maximum daily penalty for violations from $1,000 to $15,000, and eliminated the $10,000 cap on the maximum total penalty.

States outside the Intermountain region have similar issues regarding fines: North Dakota (N.D. Cent. Code § 38-08-16.1) sets the maximum penalty for violations at $12,500 per day. Since so much gas (28%) is lost to flaring in North Dakota, the state is considering stricter enforcement to lower that number. Pennsylvania (Pa. Cons. Stat. § 58-32(E)) addresses enforcement. Subsection 3256 sets penalties in conventional oil and gas development at a maximum of $25,000 plus $1,000 per day. Penalties in unconventional development are set at $75,000 plus $5,000 per day.

|

Challenges of Federal and State Monitoring and Compliance

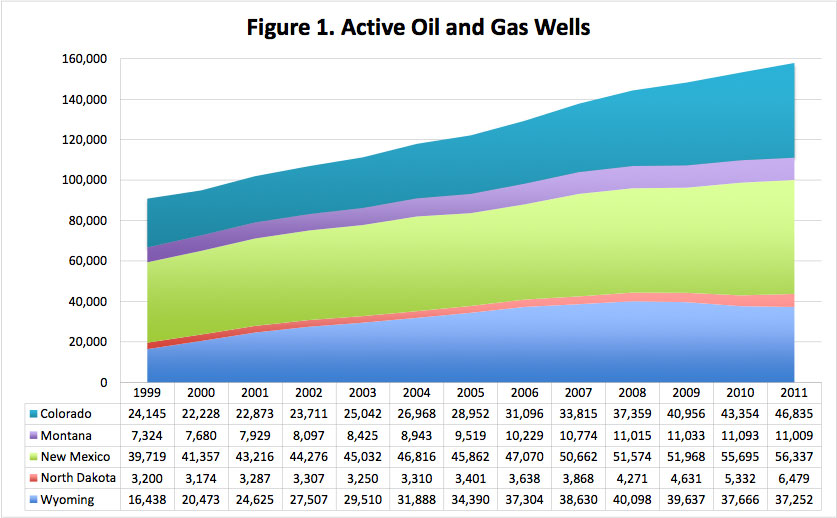

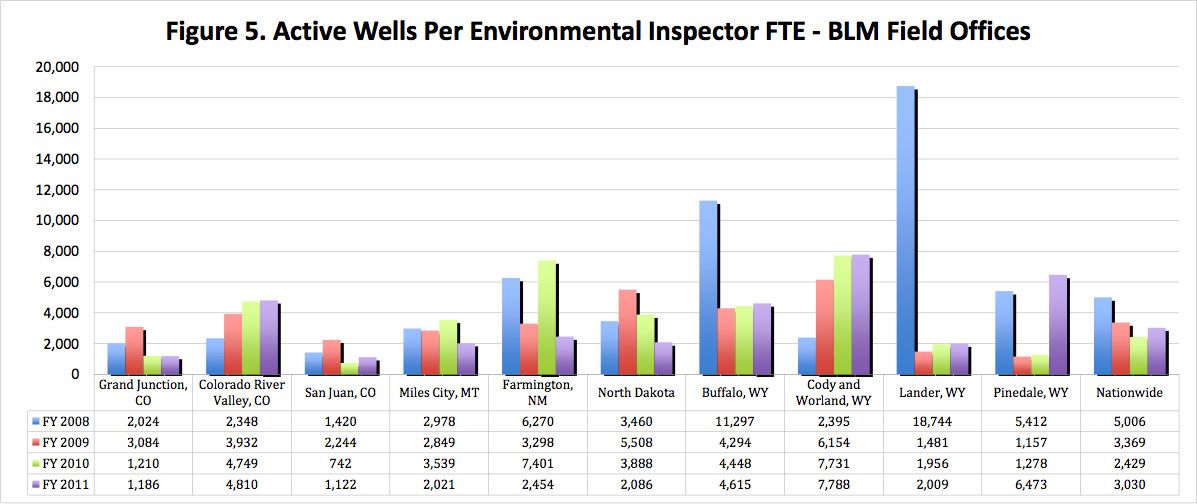

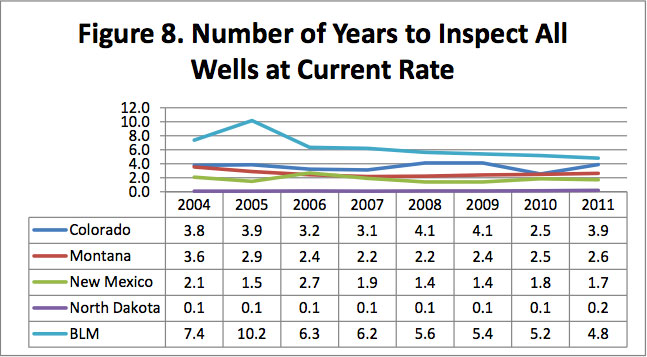

In 2013, the Western Organization of Resource Councils updated its “Law and Order in the Gas Fields: A Review of the Inspection and Enforcement Programs in Five Western States.” This report focuses on Colorado, Montana, New Mexico, North Dakota, and Wyoming. Its major findings included that inspection mechanisms are not keeping pace with increased oil and gas development in recent years. Additionally, most agencies do not have enough inspectors to conduct sufficiently frequent and thorough inspections. It also found that only Colorado and New Mexico have significant amounts of information that is easily accessible to the public. Significantly, it found that penalties are set so low as to be a completely ineffective deterrent. Several of the charts and graphs from this report are reproduced with permission below. “FTE” means “full-time equivalent” and is used to accurately calculate hours worked (always for BLM inspectors, and otherwise if indicated).

Beyond Federal and State Enforcement

While strong federal and state enforcement mechanisms are essential to assure compliance with regulatory programs, the public and oil and gas operators can also play important roles is assuring protection of communities and the environment.

Public Participation

As with most administrative agencies, state oil and gas agencies typically allow for public hearings and comments for setting the standards during agency rulemakings. Since agencies do not always have the resources or political incentives to pursue alleged violations of these rules, citizens may sometimes file forms or bring lawsuits to either force the state agency to act, or to directly enjoin the operations of the company in question. Of the intermountain states, Colorado, Montana, and Utah have the most robust mechanisms for community participation. Wyoming, by contrast, has no provision for citizen action beyond comment and hearings.

Third Party and Industry Programs

Some oil and gas companies are starting to develop internal standards. Often, these are intended to utilize existing programs, as with FracFocus, mentioned above. Industry groups, research groups, and non-profit organizations can also be helpful in providing guidance on monitoring and compliance. By encouraging companies to publicly disclose information, they can pave the way for constructive dialogue with communities. Since these organizations lack enforcement power, they focus on providing best practices for voluntary reporting.

Which companies disclose their practices and progress in reducing the risks of hydraulic fracturing? See Disclosing the Facts 2014: Transparency and Risk in Hydraulic Fracturing

Carbon Disclosure Project (CDP)

CDP solicits reports from companies on their climate change, supply chain, water, and forest impacts. Noble Energy participates in the Carbon Disclosure Project, as does Anadarko.

Center for Responsible Shale Development (CRSD)

CRSD has 15 performance standards, which are available here. Performance Standard 6 details a BMP for monitoring water quality. Performance Standard 7 recommends disclosure of hydraulic fracturing chemicals. Here is a comparison of CRSD’s standards to regulatory standards in the Appalachian Basin (Pennsylvania, West Virginia, and Ohio). The CRSD’s third party auditing program is detailed here. Here, it is suggested that CRSD standards could become as effective and influential as LEED.

Houston Advanced Resource Center (HARC)

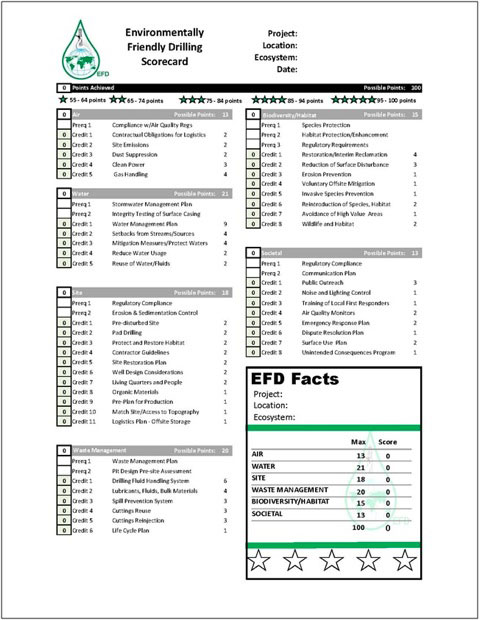

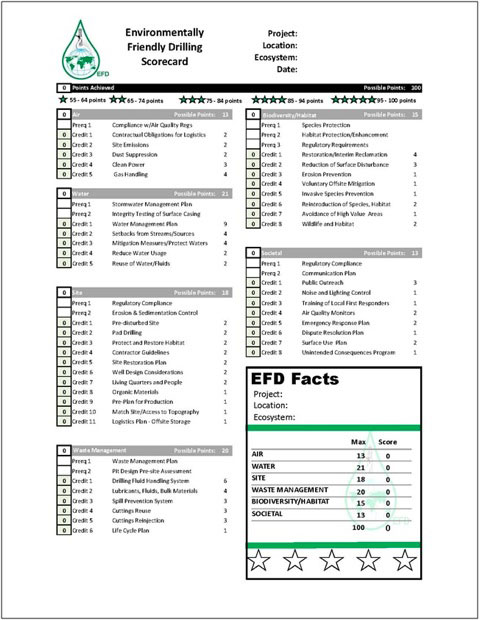

HARC’s Environmentally Friendly Drilling Scorecard provides third-party certification for companies. This provides more accountability and objectivity than a company’s internal standards would.

Global Reporting Initiative (GRI)

GRI provides sustainability guidelines for companies. Its voluntary reporting framework is detailed here and its specific Oil and Gas Sector Disclosures here. Together, they make up the recommended reporting framework for the oil and gas sector..

Global Environmental Management Initiative (GEMI)

GEMI develops “environmental sustainability solutions for business.” It regards voluntary reporting as a key component of developing transparency.

International Petroleum Industry Environmental Conservation Association (IPIECA)

IPIECA is a major industry association and the primary industry contact with U.N. It provides guidance on how to develop voluntary sustainability reporting. The IPIECA worked with IOGP and the American Petroleum Institute (API) to produce its Oil and Gas Industry Guidance on Voluntary Sustainability Reporting. This guide provides best practices for reporting on environmental impacts, climate change, health, safety, and community engagement.

Independent Energy Standards Corporation (IES)

IES is an independent analytics provider for risks and responsibilities in the oil and gas industry. IES has developed its TrustWellTM Ratings System to evaluate responsible gas and energy use. The corporation developed this system by evaluating a wide range of impacts and risks, including those related to water, air, land, and community. In addition to evaluating a producer’s operation, the system provides a range of analytics to assist the producer to identify, prioritize and implement actions for continuous risk and impact reduction. Additional information concerning this system is detailed here and a sample of IES TrustWellTM rating report here.

State Review of Oil & Natural Gas Environmental Regulations (STRONGER)

STRONGER is a multi-stakeholder organization that aims to help states improve their oil and gas environmental regulatory programs. Its standards include compliance at 4.1.2 and enforcement at 4.1.3. Of the intermountain states, STRONGER has conducted its review process in Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico.

Unlike the above organizations, STRONGER provides best practices for states. With regard to compliance, STRONGER recommends independent, frequent inspections. It also recommends state follow-up in response to public complaints. STRONGER’s proposed enforcement standards differ from existing state standards in recommending more enjoining of violators, rather than solely imposing ineffectively small fines.

|